A Blended Solution: Business correspondence training for travelling Business English learners

Introduction

In this essay, I discuss the potential application of a blended approach to Business English teaching. As a corporate trainer, delivering in-company training, I have come to accept that learners are often unable to attend lessons regularly due to professional commitments and the need to travel for business purposes. I begin with a case study, which is a typical scenario in my teaching context. In this example, I note that it was the writing element of the course that suffered mostly from attendance issues. My reflection on this instance suggested that face-to-face lesson time could be maximised for speaking activities and that the writing element of a course could occur away from the training room. Now, writing is a time-consuming exercise, and writing practice is often set by teachers as homework. However, this does not imply blended learning. What appeared viable was to move the entire writing element of a course to a virtual learning environment (VLE), including the presentation of content, the writing practice, and the feedback. I discuss my course design decisions in terms of context, technology, and learning theory below. In conclusion, I turn to the subject of assessment and consider how this could be approached in my proposed course.

Case Study

The Bank of Ayudhya is one of the largest commercial banks in Thailand, ranking as the nation’s fifth-largest financial institution in terms of assets, loans, and deposits. The bank was established in 1945 in Thailand’s former capital, Ayudhya, and then moved its head office to Bangkok in 1970. Its distribution network includes 595 domestic branches, 4 overseas branches, and 12,400 dealerships. The Bank of Ayudhya’s major shareholder, with a stake of 32.93%, is the American corporation, GE Capital International Holding (Wikipedia 2014).

Having been invited to teach in-company Business English lessons at the bank’s head office, a needs analysis undertaken during my initial meeting highlighted that training was required for 10 in-service employees of intermediate level in English. The main requirements were for active skills. In terms of speaking, the employees needed to be able to conduct meetings effectively and deliver spoken presentations. In terms of writing, the employees had to produce a range of business correspondence in their normal daily duties.

I was asked to design a 40-hour training package. The training was delivered over two 2-hour evening sessions per week over 10 weeks. I decided to focus on speaking on the first evening of each week (5 weeks on Meetings and 5 weeks on Presentations) and to devote the second weekly session to business correspondence.

Unfortunately, I was not informed by the HR department that all of the employees regularly travelled to bank branches across Thailand. Such entailed that attendance was sporadic. Most employees did attend the speaking lesson regularly, however, attendance for the writing lesson was inconsistent. The effects of this were pronounced in the final assessment. All learners gained good results from their participation in a meeting role-play and the delivery of a business presentation. However, few came close to passing the writing assessment, which consisted of the presentation of a portfolio of different types of business correspondence that they had produced. For this reason, I began to consider how to address such a problem should it arise in the future; a situation that is quite common with in-company training. In considering a blended approach, the prospect of maximising face-to-face lesson time for speaking activities, and delivering writing training online, appeared to be viable. The flexibility of the writing element of a course would allow learners to continue their studies while being engaged in business travel.

To this end, work began on the development of an online writing course that could be employed both for the writing element of a blended course and as a stand-alone online course.

Blended Learning

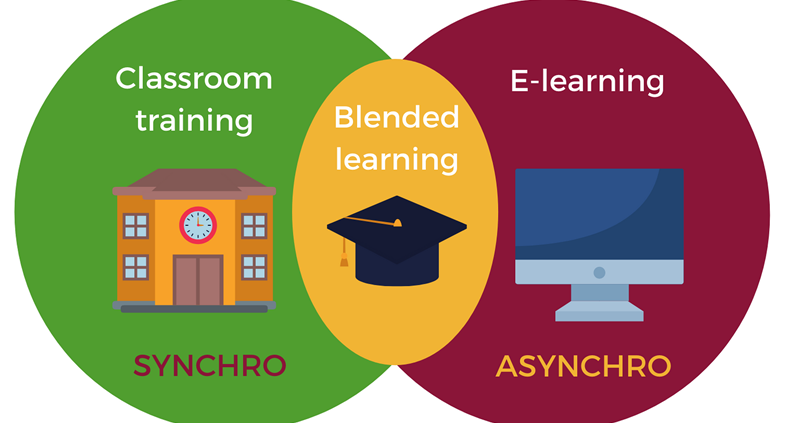

I should begin by clarifying my use of terminology. By ‘blended learning’ I imply:

- the integrated combination of traditional learning with web-based online approaches (drawing on the work of Harrison);

- the combination of media and tools employed in an e-learning environment;

- and the combination of a number of pedagogic approaches, irrespective of learning technology use (drawing on the work of Driscoll).

(Whitelock & Jelfs, 2003 cited in Oliver & Trigwell, 2005, p.17)

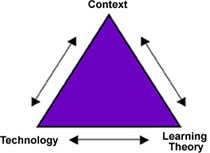

I consider these three areas of attention in terms of context, technology, and learning theory. The three elements can be illustrated in the form of a triangle, with points that are mutually informing. The issue at the top of the triangle is considered to be the strongest driver. Different scenarios call for variation in which element is the most important driver. In this example, the case study highlights that the contextual factor is key in adopting a blended approach.

Context

While Oliver and Trigwell (p.20) argue that since ‘all learning can be argued to blend contexts’ the term ‘context’ is redundant. With regard to our case study, I would disagree. Quite simply we have a context in which learners cannot attend regular face-to-face lessons. The learners regularly travel on business, and the writing element of their training can be effectively facilitated through online learning. How this can be achieved is discussed with regard to technology and learning theory.

Since I link the idea of ‘context’ with the first definition of ‘blended learning’ above, I should note that this applies to the intention of focusing on speaking in face-to-face lessons and pursuing business correspondence training online. This essay concentrates mainly on the writing element and the development of courseware, which cannot strictly be viewed as blended learning in isolation. Such would be the case if part of the writing training were to occur in the classroom, however, this would defeat the purpose of providing separate, stand-alone training as demanded by the context. A more accurate term for the writing element would be ‘flexible learning’, by which I mainly imply the ability of learners to pursue their training with flexibility of time and pace, although this extends to other considerations such as flexibility for different learner types (Chen, 2003). Such considerations will be discussed presently by reference to learning theory.

Technology

Continuing with our triangular model, consideration of technology is informed by the context and the learning theory, as it, in turn, informs in reciprocation.

In terms of context, it is important to consider what technology is available to learners, as well as issues of accessibility, connectivity, and digital literacy. With reference to our case study, the learners all had laptop computers, which they were supplied with by the Bank so as to be able to stay connected while they were away from the office. While away from home, the learners were able to get online either from the branches they were visiting or via Wi-Fi access at their hotels. This tends to be a standard scenario for business travellers, although it should never be assumed. Clarifying access issues is essential before adopting a blended or flexible approach, as we shall see below with reference to Salmon’s Five-Step Model.

In terms of learning theory and courseware design, decisions are made as to what format, or formats, are most effective for the learning experience. This must also be considered with regard to the context of the learners and the available technology. In this instance, Moodle was chosen as the hub of the training since learners are easily able to access this platform with Wi-Fi connections to their laptops in any location. The issue of literacy or, put more simply, learners’ ability to use Moodle, was a factor in the courseware design, as will be detailed below.

I refer to Moodle as ‘the hub’ because, while it can be very effective as a central core for the online learning experience, different tools that can be embedded within, or linked from, Moodle offer greater learning opportunities. For example, we shall later discuss the use of e-portfolios as an assessment option. Godwin-Jones (2008) suggests that creating an e-portfolio in closed systems, such as Moodle, ‘limits its use and may defeat the goal of establishing a mechanism for life-long documentation of learning and achievement. For this reason, a decision was made to host the assessment outside of Moodle, using an alternative tool. Such is an example of our second definition of blended learning as the combination of media and tools used in an e-learning environment.

As we explore learning theory and courseware design, we shall note other examples of a blended technology approach, primarily as a response to catering to different learning styles.

Learning Theory and Courseware Design

Our third definition of blended learning mentions the combination of a number of pedagogic approaches. My experience of courseware design to date has been largely influenced by a key selection of authors, in whose work I find both crossover points and gaps in one’s model that are accommodated by the work of their peers.

Salmon’s Five-Step Model

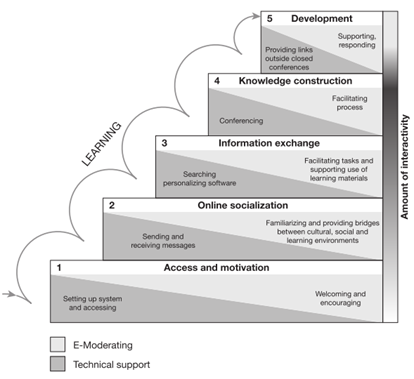

Salmon’s (2011) Five-Step Model really comes into play in filling a gap in other models, which is to begin by ensuring that learners can gain access to the learning resource and that they are able to use it. Other models seem to simply assume that this is the case, and that can become problematic.

Salmon’s first step is entitled ‘Access and Motivation’ (pp.33-35). This can be approached, in part, before a course commences by sending learners a pre-course questionnaire and an introduction to the course and the VLE. This allows any potential problems to be highlighted and addressed before the course commences.

This first step remains the focus as the course begins. In terms of motivation, a friendly welcome and some non-threatening activities that encourage participation are important in setting a positive tone. Meanwhile, as exemplified in the Unit One tasks of the courseware, these engaging tasks require participants to make use of various features within Moodle such that they are exposed to the system rather than trained (p.34). The course tutor can gauge learners’ ability to use the system simply by checking that everyone has completed each task.

Unit One tasks also involve learner-learner interaction, both within discussion forums and by direct email. These tasks are not directly associated with the course topic but are designed to enhance the well-being of the group through mutual respect and support. ‘In this way, intrinsic motivators will gradually emerge, and learning will be promoted’ (p.36). This marks the move to Stage Two, which continues through to the next unit. In Unit Two, socialisation is encouraged more in terms of collaborative learning.

Stage Three is represented in each of the ensuing units both in the form of materials that introduce and provide guidance on writing the various types of correspondence and also in the exchange of ideas between learners that is facilitated by the unit’s tasks. Following the unit input, learners write an example of the business correspondence, upload it to Moodle, and their writing is checked by the tutor. The work is not corrected by the tutor, but errors are highlighted with a correction code. For example, a verb written in the wrong tense is marked ‘WT’.

Last week I send WT an application …

The document is then returned, and the learners placed in groups to collaboratively correct the highlighted errors. This facilitates the knowledge construction of Stage Four, which can also be considered in terms of social constructivism.

The course concludes with an assessment in the form of an e-portfolio. Learners are encouraged to continue building their e-portfolios beyond the completion of the course and are provided with details of where they can seek further guidance. Here the aim is for learners to continue developing their writing skills autonomously, which is key to the final Stage of development.

The Community of Inquiry Framework

In Salmon’s model, interaction is an important aspect of the online learning experience. This necessity is also stressed in the Community of Inquiry framework (Garrison, Anderson & Archer, 1999), which considers interaction in terms of exchanges between the learner and tutor (teaching presence), between the learner and the course content (cognitive presence), and between the learners themselves (social presence).

In the business correspondence course, social presence is stimulated as discussed with regard to Salmon’s first two stages. Climate setting is the main aim of Unit One, and the regular use of forums throughout the course is geared towards supportive discourse. The importance of learner-learner interaction cannot be understated. Online courses that do not encourage learners to participate regularly by interacting with peers lose out on a valuable element of the online educational experience. Social presence ‘[empowers] participants to actively construct their knowledge rather than passively receiving information, through participation in reflective dialogue in a trusting, familiar, informal and empathic community (Chapman, Ramondt & Smiley, 2005).

A review of the literature on learner-learner interaction by Donald, Gallahad, and Kamal (2013) was a further influence on the course design since this highlights the important role social presence plays in online education.

Teaching presence implies that learners gain a sense that their tutor is a real person who has a genuine interest in the students’ development. In the courseware, this is initially approached by including a photograph and brief biography in the welcome message. Presence is strengthened by posting regular responses to the forums, and of course, learners receive some one-to-one attention through the marking of written work. Presence is also maintained in terms of the content. Each unit has at least one video tutorial.

Content selection is where teaching presence and cognitive presence merge in the framework. The course itself is based upon Lougheed’s (2003) business correspondence guide, however, it would not be productive to simply reproduce this material in an online format. Therefore the framework prompted changes to the material to allow for a variety of activities that cater to different learning styles, and the design of activities that facilitate supportive discourse.

Gardner’s Multiple Intelligences Theory

With the aim of including a variety of activities that cater to different learning styles, inspiration came from Gardner’s (1983) multiple intelligences theory. Gardner proposes that intelligence should be considered in terms of a range of abilities, rather than as being dominated by a single general ability. It can be assumed that among any group of learners a range of intelligence types will be represented, therefore educational activities should be designed to suit a range of abilities and interests. Consideration of this point guided the course design.

- Musical intelligence: Background / introductory music to set a positive mood. Spoken text.

- Kinaesthetic intelligence: Matching activities, games, online simulations

- Mathematical / Logical intelligence: Charts, tables, process guides

- Linguistic intelligence: Forums, chats, supplementary reading

- Spatial intelligence: Visual diagrams, games

- Intrapersonal intelligence: Solitary activity, element of choice, writing

- Interpersonal intelligence: Forum discussion, peer feedback, collaboration

Gagne’s Nine Levels of Learning

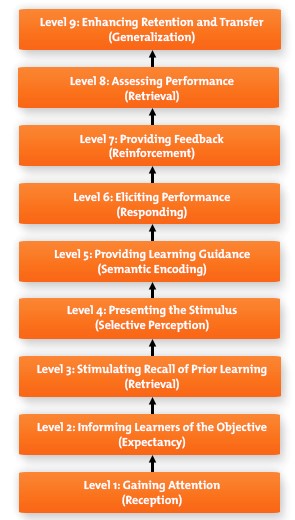

Gagne’s nine levels of learning (Mind Tools, 1996) were also referred to in the course design:

Attention (1) is gained through the welcome messages and the attractive, clean design of the course Moodle. Each unit has its own introduction, which is clearly marked (‘READ THIS FIRST’) and informs the learner of each week’s objective (2). Unit 1 has a simple email writing task, and later units begin with some reference to prior units to stimulate recall of prior learning (3). The stimulus that is presented (4) takes a variety of forms to cater to different learning styles, as mentioned earlier, and clear instructions and examples are provided at each stage to provide learning guidance (5). Performance is elicited (6) in each step of the course after the learning input, and this includes multimedia activities, forum discussion, and actual writing practice. Feedback is provided (7) throughout the course, both in terms of responding to forum posts and in marking written work, and some activities exist specifically to foster peer feedback. The final draft of each unit’s written work will be added to an e-portfolio, and this will be used for assessment (8). The e-portfolio will be a permanent record, and learners will be encouraged to continue developing this to enhance retention and transfer (9), as was discussed in terms of Salmon’s fifth stage.

Assessment

Finally, let us turn our attention to how the learners will be assessed. Assessment of this course takes account of different learning perspectives. On one level an associative perspective is interested in how learners bring together component skills that are taught on the course to produce examples of business correspondence. This is partly summative as a piece of writing must be submitted each week. However, these examples are not graded, but are returned with highlighted errors and then corrected collaboratively. So a social constructivist perspective appears, which emphasises that ‘feedback is not just teacher-provided but must be rich and varied, deriving also from peers during collaboration and discussion’ (JISC, 2010). A key point here is that the final submission of an e-portfolio comprised of the final drafts of the collaboratively corrected documents is not intended as a summative assessment in the usual sense. Ten examples of writing that are, in part, the work of a group cannot be held to assess individual mastery of business correspondence in all its forms. The focus is more on providing a good foundation from which learners can develop their writing skills autonomously. Of more value to a student’s learning is the comparison of their first and final drafts, than in achieving a grade. Therefore 80% participation, including contributing to the forums, achieves a ‘pass’.

So much for the theory … let’s experience it in practice …

“I felt so inspired by this course, which I learned so much from. It gave me a better perception of online teaching.”

Margo in South Africa

If you think ‘teaching online’ just means live lessons in a virtual classroom or Zoom, then get ready to think again!

Our comprehensive course on effective Online Course Delivery is now enrolling. Designed by industry experts with years of experience in online education, this course is tailored to help you develop and deliver effective, engaging online courses that inspire your learners and foster their success.

In this course, you will learn:

- The principles of effective online course delivery

- How to develop clear and measurable learning outcomes

- Strategies for engaging and motivating your learners

- How to design effective assessments and evaluations

- Tips for creating interactive and multimedia-rich content

- Techniques for promoting learner interaction and collaboration

- Best practices for managing online discussions and feedback

Our course is designed for educators and course creators of all levels, from beginners to experienced professionals. With a mix of online lectures, interactive activities, and real-world examples, you’ll gain the skills and confidence you need to create courses that truly make an impact.

Don’t miss out on this opportunity to take your online courses to the next level!

Enroll now and start delivering effective, engaging online courses that inspire your learners and drive their success!

Course length, dates & times

This 35-hour course is delivered over 5 weeks. There will be a weekly 1-hour live session, the timing of which will be negotiated per the availability of the group.

Apart from the live session, much of the interaction takes place in online forums. Participants can log in and work through each unit at any time during the week.

!! SPECIAL OFFERS !!

Book Online Course Delivery + Teaching Business English

and get £33 off the standard price

Register Now …

”I enjoyed Online Course Delivery immensely. The training provider has designed a detailed course that gives fantastic value for money, incorporating both individual and group forms of communication and tasks. The course has given me the knowledge and tools to further my career teaching online. I can highly recommend Online Course Delivery.”

Matt in Brazil

REFERENCES

Chapman, C., Ramondt, L. and Smiley, G., 2005. Strong community, deep learning: exploring the link. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 42(3), 217–230.

Chen, D., 2003. Uncovering the Provisos behind Flexible Learning. Educational Technology & Society, 6(2), pp.25-30.

Donald, R., Gallahad, R. and Kamal, S., 2013. Social presence and learner-learner interaction: their role in fostering deep learning in online education. [online] DigiTEFL. Available at: https://mrbee.uk/what-is-the-importance-of-social-presence-in-fostering-deep-learning/ [Accessed January 2014].

Gardner, H., 1983. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. New York. Basic Books.

Garrison, D.R., Anderson, T. and Archer, W., 1999. Critical Inquiry in a Text-Based Environment: Computer Conferencing in Higher Education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2(2-3), pp.87-105.

Godwin-Jones, R., 2008. Web-Writing 2.0: Enabling, Documenting and Assessing Writing Online. Language Learning & Technology, 12(2), pp.7-13.

JISC, 2010. Effective Assessment in a Digital Age. [pdf] Bristol: JISC. Available at: http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/programmes/elearning/digiassass_eada.pdf [Accessed January 2014].

Lougheed, L., 2003. Business Correspondence: A Guide to Everyday Writing. 2nd ed. New York: Pearson.

Mind Tools, 1996. Gagne’s Nine Levels of Learning. [online] Available at: < http://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/gagne.htm> [Accessed January 2014].

Oliver, M. and Trigwell, K., 2005. Can ‘Blended Learning’ Be Redeemed? E–Learning, 2(1), pp.17-26.

Salmon, G., 2011. E-moderating – The Key to Teaching and Learning Online. 3rd ed. London: Taylor & Francis.

Wikipedia, 2014. Bank of Ayudhya. [online] Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bank_of_Ayudhya [Accessed January 2014].